- Kingdom leads Gulf’s satellite sector

- Safe disposal of space assets ‘critical’

- Junk in orbit threatens communications

Saudi Arabia is targeting lucrative and environmentally critical opportunities in the rubbish removal sector – in outer space.

More than 27,000 man-made objects larger than 10 centimetres, such as defunct satellites and spent rocket stages, orbit Earth, according to Nasa.

This space debris puts at stake billions of dollars of assets such as spacecraft and satellites which support modern communication and security systems.

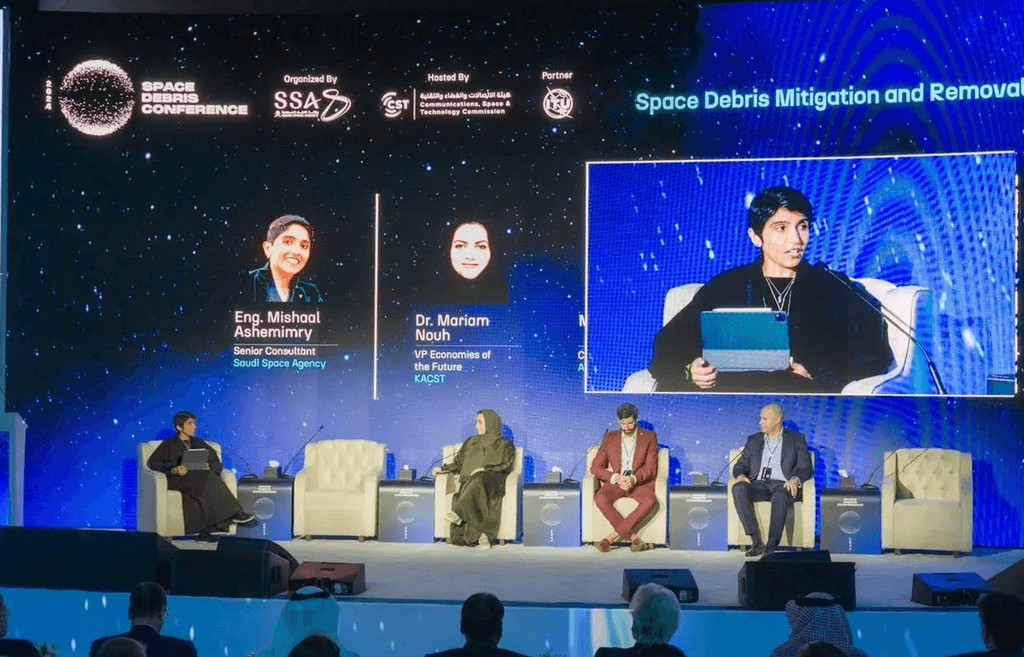

Mishaal Ashemimry, the Gulf’s first female aerospace engineer and the first woman of Saudi origin to work with Nasa, is special adviser to the CEO of the Saudi Space Agency.

She told AGBI that the issue of space debris, while not new, is escalating in urgency, fuelled by the surge in satellite launches and consequent space traffic concerns.

“The more you put in space, the more you’re going to have to worry about traffic, avoidance and procedures to ensure new or existing satellites don’t collide with junk,” she said.

- US-Saudi venture will use AI to analyse space data

- Saudi CubeSats could send green monitoring into orbit

- Saudi Arabia signals intent with space sector shake-up

“If you don’t have a means to get rid of non-functioning satellites, or extend their life, you’re posing a really huge threat to future space efforts.”

Polaris Market Research, a US-based company, projects the global market for space debris monitoring and removal to expand from $940 million in 2022 to over $2 billion by 2032, at about an 8 percent annual growth rate.

Ashemimry said that addressing space debris is in the best interests of all asset owners, and that mitigation needs both regulatory and commercial efforts.

The Saudi Space Agency in February hosted the first Space Debris Conference in Riyadh, during which it entered a research collaboration with LeoLabs, a US company specialising in space monitoring to identify threats.

Saudi Space Agency

Saudi Space AgencyLeoLabs has secured $129 million across four funding rounds so far and its most recent round was oversubscribed.

The partnership also included potential Saudi investments in LeoLabs and is exploring the establishment of LeoLabs facilities and subsidiaries in the kingdom.

Saudi Arabia leads the Gulf’s satellite sector, having launched 35 out of the region’s 60 satellites, according to a report by the German company SpaceTech in 2023.

“The Saudi effort, which will grow in terms of assets in space, is that we will do so responsibly and sustainably,” Ashemimry said.

“Any satellite and any effort that we plan to put in space will have a means to deorbit or get rid of safely, such that it doesn’t pose a debris threat on future constellations.

“Coming in with this mindset and having the regulation in place is very critical for us, especially because we don’t have as many assets as the rest of the world in comparison.”

Tens of thousands of new satellites are being launched globally.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX, the world’s largest satellite operator, has launched nearly 6,000 Starlink satellites so far, with plans for a constellation of 12,000 with a possible extension to 42,000 satellites.

SpaceX says it “proactively deorbits” satellites that are at risk of becoming non-maneuverable, but that process can take up to five years, the company’s website says.

Jeff Bezos’s Amazon entered the broadband internet race this year, launching two prototype satellites for its Kuiper network. Amazon aims to rival Starlink, the world’s largest satellite operator.

The European Space Agency says on its website that it already receives hundreds of collision warnings every week for its spacecraft fleet, highlighting the growing risk space debris poses to economies and societies dependent on satellite services.

Space’s growing trash problem

Over the past six decades, about 11,000 satellites have been launched, of which 7,000 remain in space.

One problem associated with satellite mega-constellations is light pollution, which could hinder future scientific discovery.

Some scientists also believe that the deposit of hazardous levels of alumina and other man-made materials into the upper atmosphere when satellites burn up on re-entry could damage the ozone layer.

Space debris could trigger a chain of collisions, potentially encircling Earth with a dense barrier of wreckage, a scenario termed the Kessler syndrome.