Moving Beyond Lithium-Ion

Batteries have progressively become the key technological innovation of the decade, the way the previous decades were shaped by the rise of the PC or the Internet.

This is because progress in battery technology is driving not only the EV revolution but has appeared as the crucial limitation for the greening of the power grid, due to the intermittency of renewables.

Ultra-dense and/or cheap batteries are also going to be crucial to electrify and decarbonize energy-hungry sectors of the economy, like heavy industry (chemicals, metallurgy, manufacturing) and transportation (trucks, ships, planes).

So far, this has been achieved with variations of lithium batteries, either lithium-ion (lithium-nickel-manganese NMC & lithium-nickel-cobalt-aluminum NCA) or lithium-ferrum-phosphate (LFP) batteries. It was a transformative technology that rightfully earned its inventors the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (follow the link for the history of lithium-ion invention).

Until now, these batteries were expected to keep dominating the battery market, thanks to their extremely high energy density.

Source: S&P Global

Later on, solid-state batteries are considered as a possible next step to keep raising the density of batteries and also use a lot of lithium, see “5 Best Solid-State Battery Stocks to Watch or Buy”.

However, lithium is not the only ion usable in batteries. Much more abundant and cheaper sodium, the base of table salt, is a candidate as well.

The problem is that sodium-ion batteries have been lower in energy density so far, they are relegated to low-price/low-range EVs or stationary utility-scale batteries.

This might change, thanks to the invention of sodium-ion batteries using TAQ cathode. This was the work of researchers at MIT and Brookhaven National Laboratory, who published their results in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, under the title “High-Energy, High-Power Sodium-Ion Batteries from a Layered Organic Cathode”1.

Source: Princeton University

TAQ Cathode

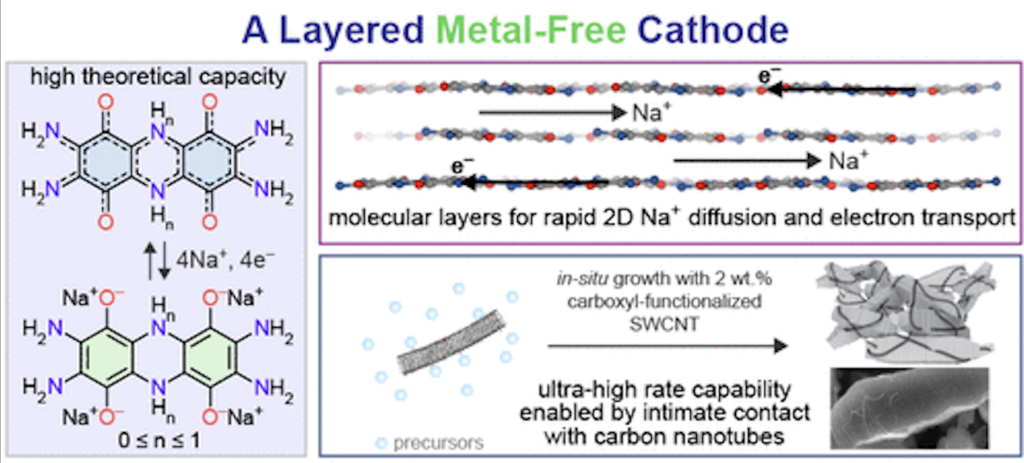

We previously reported on the TAQ cathode in “Designing a Better Battery – Out with Cobalt and In with…TAQ?“. TAQ, or bis-tetraaminobenzoquinone, is a layered organic solid compound.

In this research from 2024, the researchers discovered that TAQ had not only potential as a supercapacitor material, but outperformed traditional lithium cathode.

Source: GreenCarCongress

They found how to improve the adherence of TAQ to the cathode’s stainless-steel current collector, improving the stability of the new proof-of-concept cathode prototype.

By adding cellulose- and rubber-containing materials to the TAQ, they safely achieved more than 2,000 charge-discharge cycles. The energy density was also higher than with cobalt-based cathodes, and the charging took less than 6 minutes.

Back in 2024, we mentioned the potential for other battery chemistry to use TAQ as well:

It is also worth noting that organic cathodes have been discussed for other types of batteries as well, for example, for aluminum-ion, sodium/potassium-ion, zinc, or calcium-based dual-ion batteries. So, it is possible that the discovery of TAQ’s properties can be applied to other battery types than lithium-ion.

And this is exactly what the research team did, creating an ultra-high energy density sodium-ion battery.

TAQ Sodium-Ion Battery

Why Sodium?

The reason for the researchers to have picked sodium for the next step of their research is how abundant the material is.

“It’s always better to have a diversified portfolio for these materials. Sodium is literally everywhere. For us, going after batteries that are made with really abundant resources like the organic matter and seawater is among our greatest research dreams.

Being on the front lines of developing a truly sustainable and cost-effective sodium ion cathode or battery is truly exciting.”

Mircea Dincă – Professor of Chemistry at MIT.

There is also a business rationale as this study, as well as the 2024 initial study on TAQ, has been funded by Automobili Lamborghini S.p.A. Cheaper materials and battery technology that is not dependent on a China-dominated supply chain could be a savior for a somewhat struggling European car industry, which is lagging when it comes to electrification.

Adapting TAQ Cathode to Sodium Batteries

To make it work with sodium, the researchers had to modify their design to match the requirements of sodium-ion batteries.

One challenge was to create a homogeneous electrode containing both TAQ and carbon.

“The binder we chose, carbon nanotubes, facilitates the mixing of TAQ crystallites and carbon black particles, leading to a homogeneous electrode. The carbon nanotubes closely wrap around TAQ crystallites and interconnect them.

Both of these factors promote electron transport within the electrode bulk, enabling an almost 100% active material utilization, which leads to almost theoretical maximum capacity.”

Dr. Tianyang Chen – MIT Researcher

Source: Princeton University

High Performances

This extremely high capacity achieved on a prototype could quickly convert into very efficient batteries, especially regarding charging time, a regular limitation of EVs, and complaints of consumers.

“The use of carbon nanotubes considerably improves the rate performance of the battery, which means that the battery can store the same amount of energy within a much shorter charging time, or can store much more energy within the same charging time.”

Dr. Tianyang Chen – MIT Researcher

This was achieved while keeping the advantages of TAQ, namely stability against air and moisture, long lifespan, ability to withstand high temperatures, and environmental sustainability.

The final product was a cathode energy density of 472 Wh/kg electrode when charging/discharging in 90 s and a top specific power of 31.6 kW/kg electrode.

For reference, this is somewhat close to the density of commercial Ni/Co-based layered cathodes (∼740 Wh/kg-cathode) referenced in a 2024 scientific publication.

Future Developments And Commercial Potential

Overall, it is likely that high-end lithium-ion and, later on, solid-state batteries will keep controlling the high-end EV market.

However, for more price-sensitive segments like low- and mid-range EVs, commercial trucks, utility storage, etc., other factors will likely be more important, like overall cost, availability of resources, durability, etc.

This could put a cap on lithium demand, as sodium is increasingly shaping into a viable alternative, thanks to innovative cathode materials like TAQ.

Other improvements could contribute as well, for example, removing the need for an anode entirely (the other end of the battery), as we discussed in July 2024 in “Anode-Free Sodium Solid-State Batteries Could Reduce Reliance on the ‘Lithium Triangle’.”

Source: University Of Chicago

This has not been tested yet, and will likely require some tinkering, but we can easily imagine in the long run that most EVs and commercial trucks will not need massive 1,000-2,000-mile range batteries using the best possible solid-state lithium battery.

Instead, a future anode-free, TAQ-cathode sodium battery, maybe solid-state, maybe sodium-ion, will be enough to reach the 400-600 miles range capacity at a better price.

Besides innovation in chemistry, structural design can also improve batteries, like the honeycomb structure used in the “condensed state” battery from CATL, the largest battery producer in the world. Maybe such an idea could be deployed to sodium-ion batteries as well. (see more information in “CATL (300750.SZ): The Battery Juggernaut”).

Investing In Advanced Battery Technologies

Batteries are at the center of the trend of electrification, itself a major multi-trillion-dollar endeavor looking to remove fossil fuels from our power sources.

You can invest in battery-related companies through many brokers, and you can find here, on securities.io, our recommendations for the best brokers in the USA, Canada, Australia, the UK, as well as many other countries.

If you are not interested in picking specific battery companies, you can also look into battery ETFs like Amplify Lithium & Battery Technology ETF (BATT), Global X’s Lithium & Battery Tech ETF (LIT), or the WisdomTree Battery Solutions UCITS ETF, which will provide a more diversified exposure to capitalize on the growing battery industry.

Organic Cathode Company

Volkswagen AG

The research of Pr. Mircea Dincă on TAQ cathode, both in 2024 (lithium-ion) and 2025 (sodium-ion), was funded by Automobili Lamborghini S.p.A., a subsidiary of Audi, itself owned by the Volkswagen Group.

A patent application for the organic cathode technology has been filed.

The German automaker is the second-largest car producer in the world, behind only Toyota. The company was, for a time, lagging in EV technology but has worked hard to catch up since, notably with the ID car series and multiple hybrid models as well.

Source: Volkswagen

The collaboration with the MIT researchers is just one among many, with other partnerships about EVs including:

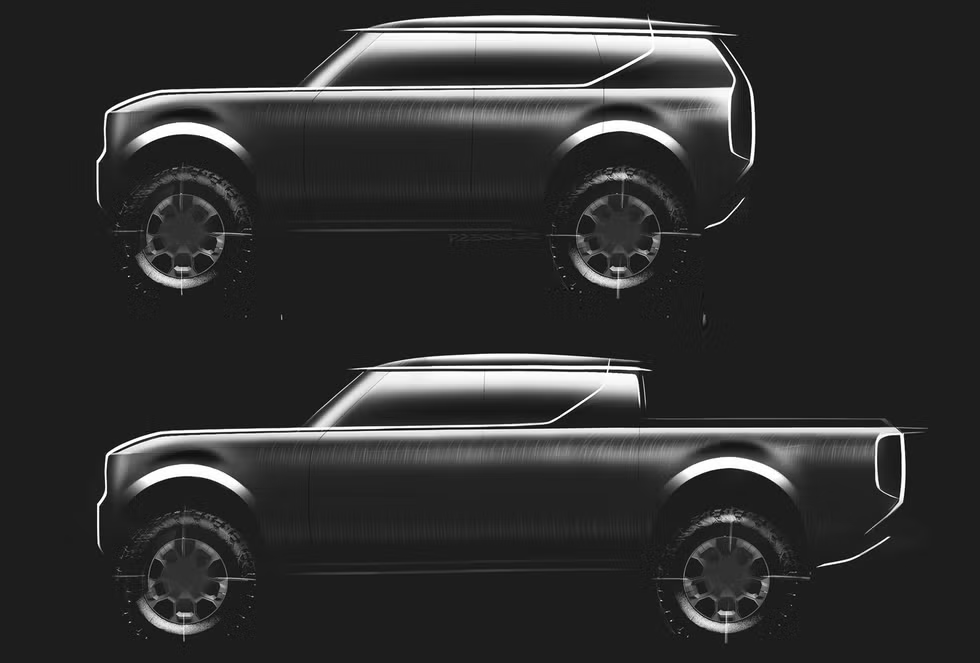

Scout cars – Source: Volkswagen

With its ambitious plans regarding EVs and access to advanced EV technology from leading Chinese companies, Volkswagen is in a good position to look at MIT’s organic cathode patented technology and work on deploying it at scale in its future EVs.

It might, however, in the meantime, look to first focus on hybrids and keep ICE cars longer than initially planned in order to “maintain flexibility”.

You can read more about Volkswagen and its EV strategy, including the fixing of its software issues through a deal with Rivian, and the unification of EV architecture throughout the Volkswagen Group and its brands in “Volkswagen Closing German Factory? What’s Next for the Troubled Automaker?”.

Study Reference:

1. Chen, T., Wang, J., Tan, B., Zhang, K. J., Banda, H., Zhang, Y., Kim, D.-H., & Dincă, M. (2025). High-energy, high-power sodium-ion batteries from a layered organic cathode. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 147(7), 6181–6192. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c17713