Nobel Prize History

The Nobel Prize is the most prestigious award in the scientific world. It was created according to Mr. Alfred Nobel’s will to give a prize “to those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind” in physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature, and peace. A sixth prize would be later on created for economic sciences by the Swedish central bank.

The decision of who to attribute the prize to belongs to multiple Swedish academic institutions.

Legacy Concerns

The decision to create the Nobel Prize came to Alfred Nobel after he read his own obituary, following a mistake by a French newspaper that misunderstood the news of his brother’s death. Titled “The Merchant of Death Is Dead”, the French article hammered Nobel for his invention of smokeless explosives, of which dynamite was the most famous one.

His inventions were very influential in shaping modern warfare, and Nobel purchased a massive iron and steel mill to turn it into a major armaments manufacturer. As he was first a chemist, engineer, and inventor, Nobel realized that he did not want his legacy to be one of a man remembered to have made a fortune over war and the death of others.

Nobel Prize

These days, Nobel’s Fortune is stored in a fund invested to generate income to finance the Nobel Foundation and the gold-plated green gold medal, diploma, and monetary award of 11 million SEK (around $1M) attributed to the winners.

Source: Britannica

Often, the Nobel Prize money is divided between several winners, especially in scientific fields where it is common for 2 or 3 leading figures to contribute together or in parallel to a groundbreaking discovery.

Over the years, the Nobel Prize became THE scientific prize, trying to strike a balance between theoretical and very practical discoveries. It has rewarded achievements that built the foundations of the modern world like radioactivity, antibiotics, X-rays, or PCR, as well as fundamental science like the power source of the sun, the electron charge, atomic structure, or superfluidity.

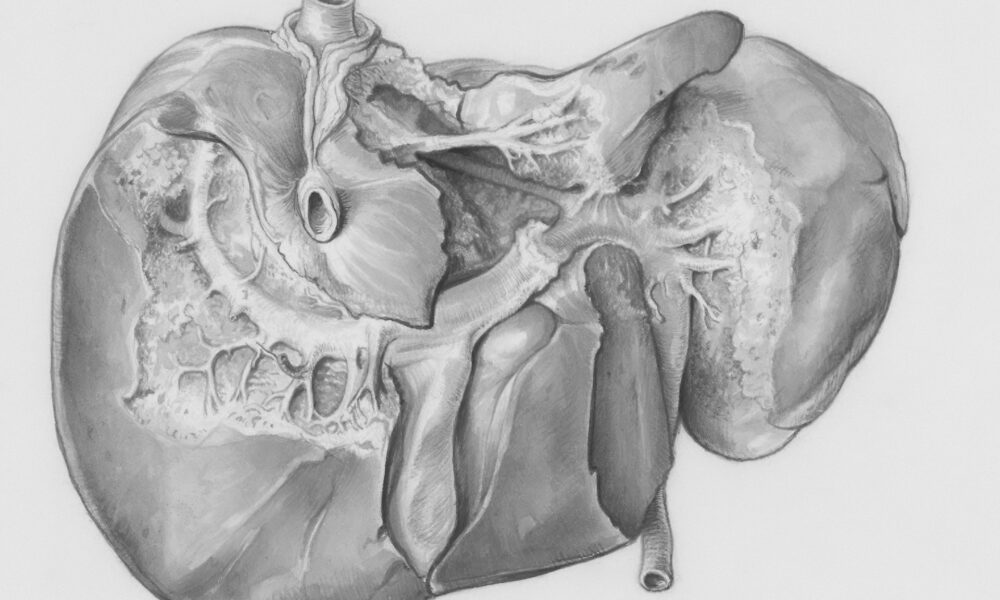

Understanding Hepatitis

Hepatitis is a silent killer, with the damage it causes to the liver often going unnoticed for years until it is too late to save the patient. The disease has long been mysterious, as it can be caused by multiple factors.

One source of hepatitis is lifestyle and environment, with alcohol abuse or toxins potentially damaging the liver and causing hepatitis. In some rarer cases, it can also be caused by autoimmune diseases. However, a third category exists, which is when the liver is damaged by pathogens.

Already in the 1940s, two types of infectious hepatitis were identified. The first type was linked to contaminated food or water and was named hepatitis A. While potentially serious in older people or in the case of a weakened immune system, it is treatable and, most of the time, has no long-term consequences, even if it can sometimes be accompanied by a recurrence of symptoms 6 months after the first outbreak.

The other type, however, is a disease that is transmitted through blood and bodily fluids. It is also a very insidious disease that can stay silent for years after contamination before any symptom manifests. When it finally manifests, it can lead to deadly liver failure and liver cancers.

And it took a long time to figure out what infectious agent caused this type of hepatitis. Even today, viral hepatitis causes more than 1 million deaths per year, putting it on par with malaria and above HIV/AIDS.

Hepatitis B Alone?

The first step in figuring out the root cause of blood-transmittable hepatitis was taken in the 1960s. Baruch Blumberg, who would later win the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1976 for his discovery of the Hepatitis B virus, took this step. The discovery resulted in the development of an effective vaccine and reliable tests.

At that time, a doctor called Harvey J. Alter was studying the occurrence of hepatitis in patients receiving blood transfers. He was also a former colleague of Hepatitis A-discoverer Baruch Blumberg at the start of his career.

Even with hepatitis B tests, contamination leading to viral hepatitis still occurred, and it became quickly clear that another pathogen than hepatitis B was responsible for some cases of viral hepatitis.

That newly identified disease was first called the “non-A, non-B hepatitis”, and is today called hepatitis C.

Source: Nobel Prize

The Long Road To Identify Hepatitis C

Three researchers were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2020 for identifying the hepatitis C virus. Each brought a key individual contribution to finding the virus causing this disease:

- Harvey J. Alter proved that there was another virus than hepatitis B, contaminating blood transfusions and causing deadly chronic hepatitis.

- Michael Houghton used a previously untested strategy to isolate the genome of the still unidentified virus.

- Charles M. Rice demonstrated without a doubt that the discovered virus was the cause of non-A, non-B hepatitis/hepatitis C.

Source: Nobel Prize

Source: Nobel Prize

The Hunt For Hepatitis C

Harvey J. Alter’s work demonstrated that only 20% of post-transfusion-associated hepatitis was prevented by the detection of hepatitis B. So hepatitis B was not the only causal agent, but it was also not the main one.

After further study, it appeared that this “non-B hepatitis” was becoming more prevalent and also different in clinical symptoms. Notably, it had at first a short incubation period, a milder form of the acute phase of the disease, and developed later on the hepatitis after a long incubation.

All the evidence Dr. Alter uncovered pointed at a second virus with a different disease profile, which has yet to be identified. He developed an animal model by finding that chimpanzees could be infected with the human non-B hepatitis disease. This animal model first helped identify the virus’s infectious capacity and, therefore, its profile. It appeared that the virus was enveloped and had a diameter of approximately 30 to 60 nm.

But for over a decade, all the known methods to identify viruses would fail to track down the hepatitis C virus.

Genomic Techniques To The Rescue

Michael Houghton, working for the pharmaceutical firm Chiron, used early forms of genomic methods to track down the virus. They performed their research using Alter’s chimpanzee model.

The first step was creating a massive collection of DNA fragments from nucleic acids found in the blood of the infected chimpanzees. However, the initial techniques used to screen for viral DNA, like enriching viral sequences or removing the DNA from complementary with an infected chimp sample, failed.

So instead, they got bacteria to express the fragments of DNA into proteins and screened through 1 million bacterial colonies until finding one that did not contain chimpanzee or human DNA sequences.

Encouragingly, the genetic sequence matched somewhat with other known RNA viruses.

Source: Nobel Prize

Further research would prove that the viral genetic sequence, when used to create a protein, was reacting to antibodies from infected chimpanzees.

Houghton’s team also developed a test for the virus and confirmed its presence in the blood of a donor that had been linked to hepatitis C contaminations.

Proving The Causal Link

The demonstration of the existence of “non-B hepatitis” was the first piece of the puzzle. And Houghton’s identification of the virus’ genetic material seemed to point in the right direction.

However, definitive proof that the virus was causing the disease and not just correlated to it was still needed. Charles Rice’s contribution to this Nobel Prize discovery would be this.

Rice identified a genetic sequence in the virus that was consistently preserved from mutation, likely indicating its importance for the infection and virus replication to occur. He then injected the viral RNA genome into the liver of chimpanzees.

After several tentatives, he managed to replicate the clinical signs of hepatitis. They found infectious virus particles in the monkey several months later, confirming that the virus’ RNA was both the cause of the hepatitis and the cause of the transmittable infection now known as hepatitis C.

The Fight Against Hepatitis C Continues

Finding the virus would prove to be the first step in developing efficient treatments against the hepatitis C virus. First, tests were developed to identify patients who were infected and stop all blood transfusion-related contamination.

Large efforts were made to develop a model that could help study the virus in a lab and controlled environment. This worked partially, with a strain of the virus working in vitro on hepatoma cell lines, as well as special mice grafted with human hepatocytes (liver cells).

Still, a vaccine would prove more elusive, and treatments took time to develop.

Source: Nobel Prize

Hepatitis C Treatments

The first breakthrough in hepatitis C therapy came from a class of drugs inhibiting the NS3/NS4A protease, a key protein for the replication of the virus. Drugs including beceprevir, teleprevir, and simeprevir were developed along this principle.

Another method targets the replication of the viral RNA, with the drugs sofosbuvir and ledipasvir, which represent a big leap in improving the medical options for the disease. Overall, these drugs can cure 95% of people with chronic infections, but the treatments have often been too expensive for all patients to use them.

As a result, hepatitis C disability worldwide tightly correlates with national wealth, with high rates in poorer developing countries.

Source: Wikipedia

Hepatitis C Vaccine

The development of a vaccine for the virus has been slow, as often for diseases with a low profile and long chronic phases, like, for example, HIV. Another factor is that there are no less than 60 subtypes of the virus, making a single vaccine unlikely to be effective against all of them.

Still, preventing hepatitis C would be both a boost to people’s health and massive saving, with 3.5 million Americans infected and $24,000-$100,000/treatment course.

One company, Inovio, is working on such a vaccine, but is still only in phase 1 of clinical trials, and also does not mention the vaccine on its R&D pipeline page.

Investing In Hepatitis Research and Treatment

Despite decades of research and multiple Nobel Prizes, the find against hepatitis is still ongoing. This is especially true for hepatitis C due to the absence of a vaccine.

You can invest in hepatitis-related companies through many brokers, and you can find here, on securities.io, our recommendations for the best brokers in the USA, Canada, Australia, the UK, as well as many other countries.

If you are not interested in picking specific companies, you can also look into biotech ETFs like the Pacer Biothreat Strategy ETF (VIRS), or the Amplify Treatments, Testing and Advancements ETF (GERM), even if there is no dedicated hepatitis or virus-only ETF available, which will provide a more diversified exposure to capitalize on hepatitis-related stocks.

Hepatitis Companies

1. Gilead Sciences

Gilead is one of the largest biotech success stories of the last 30 years. It is centered around specific therapeutic areas, with a predilection for untreated diseases, mostly in virology at first and then in oncology.

An emerging focus is also inflammation, the root cause of many other hard-to-treat diseases. Still, HIV represents by far the bulk of Gilead’s current income.

Source: Gilead

It currently has 30 approved drugs, most of them for HIV, Hepatitis (7 different therapies including previously mentioned leaders sofosbuvir and ledipasvir), and cancer. Its R&D pipeline contains 59 clinical trial programs, of which 19 are in phase 3.

Of these R&D programs regarding hepatitis, the company has a treatment for hepatitis B in phase 2 of clinical trial, a vaccine for hepatitis B in phase 1, and 2 treatments (in phase 3 and 2) for hepatitis D, another virus propagating only in the presence of hepatitis B.

The R&D programs are overwhelmingly dominated by infectious diseases and oncology clinical trials, deepening Gilead’s specialization, especially with 13 HIV-related clinical trials.

Gilead is a surprisingly “niche” biotech for its market cap. It is very focused on HIV, hepatitis, and, to some extent, oncology. Investors in Gilead might want to understand the dynamic of the HIV drug market as most of the company’s ongoing cash flow is tied to it while also not neglecting its expertise in hepatitis and other fields.

2. Roche Holding AG (RHHBY)

Roche has been a long-time leader in oncology (cancer medicine), with blockbuster drugs like Rituxan, Herceptin, and Avastin, even if these products are now getting under pressure from the commercialization of biosimilars (the equivalent of generics for biotech drugs).

The company is active in therapies and diagnostics, with 28 million people treated with Roche’s medicines annually and 27 billion Roche tests performed annually. The therapy division represents roughly 3/4th of the company’s revenues.

It is also active in hepatitis treatment with Pegasys, a medication used to treat both hepatitis B & C, sometimes in combination with other drugs. The company sells hepatitis tests as well.

Still, the oncology part of Roche’s portfolio has been steadily growing since 2018, now accounting for around a quarter of the company’s revenues. Immunology and neurosciences are other segments of importance for Roche.

The company currently has no less than 78 cancer therapies in its R&D pipeline, from a total of 161 therapies in development. Of these 78 oncology therapies in the pipeline, 2 are already approved, and 30 are in phase III of clinical trials.

Source: Roche

Roche is a very large pharmaceutical company, which is best suited for investors looking for a steady income and a relatively safe stock. It has a strong presence in the hepatitis market, including tests, but somewhat dwarfed by the size of the company’s other activities.

So, it might make the company a good pick for investors interested in investing in the market of tests for infectious diseases and oncology, which includes treatments and tests for hepatitis, but looking for a broader exposure to the pharmaceutical sector.